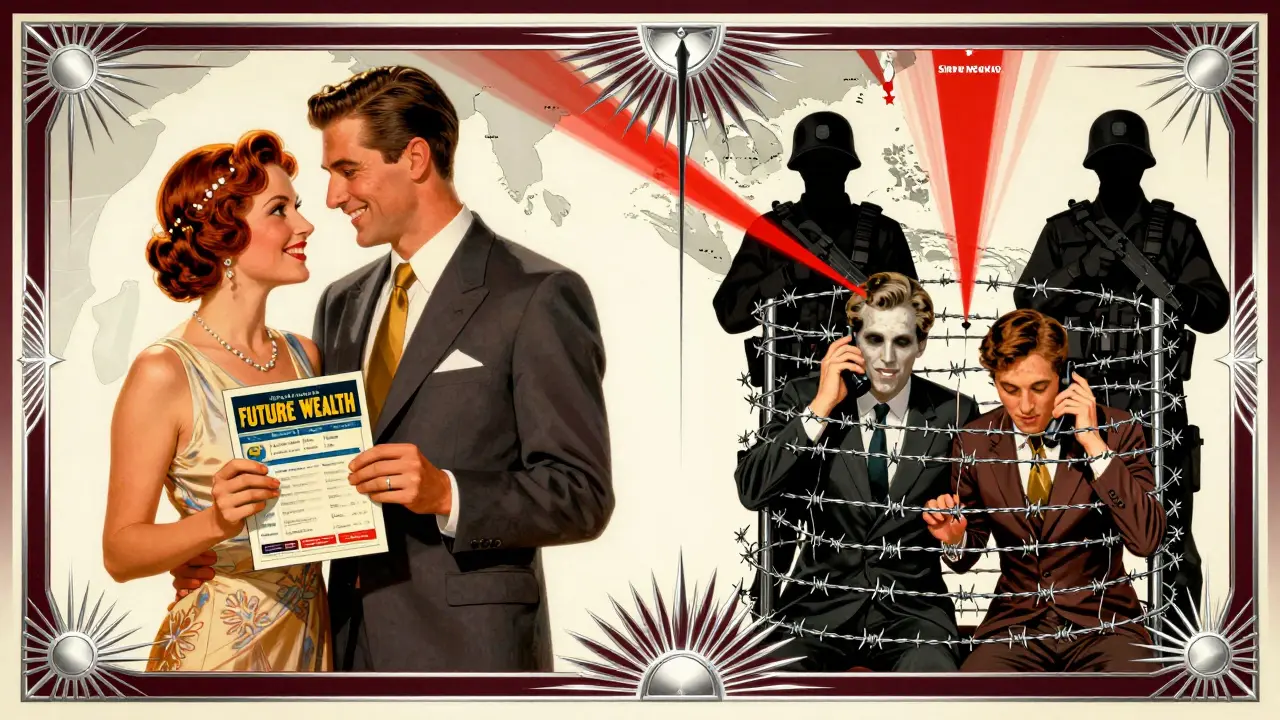

On September 8, 2025, the U.S. Treasury Department dropped a major hammer on crypto scam operations based in Myanmar. Nine entities tied to the town of Shwe Kokko were officially sanctioned, along with ten more in Cambodia. These aren’t random criminals. They’re part of a vast, organized network that’s stolen over $10 billion from Americans in just one year - 2024. And it’s not just about money. Victims are forced into labor, locked in compounds, and made to scam their own countrymen. This isn’t a hack. It’s slavery with Bitcoin.

How These Scams Work

Think of these operations like factories - but instead of making phones or clothes, they make lies. People are lured with fake job offers: "Work from home, earn $5,000 a month, no experience needed." They show up in Myanmar, only to be trapped. Their passports are taken. They’re beaten if they refuse to make calls. Their job? Convince Americans they’ve found the next big crypto investment - a fake platform, a rigged app, a phishing site that looks real. Once the money hits, it’s washed through dozens of wallets, mixed with clean funds, and vanished. The crypto part makes it hard to trace. Bitcoin, Ethereum, Tether - these aren’t like bank transfers. There’s no central authority. No paper trail. No signature. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. And the scammers know it. They use crypto because it’s anonymous, fast, and global. The U.S. government says these scams are now the biggest source of financial loss from overseas crime - bigger than drug trafficking, bigger than ransomware.Who’s Behind It

The real power behind these operations isn’t some shadowy hacker group. It’s the Karen National Army (KNA), a militia group controlling Shwe Kokko. This isn’t some backwater village. It’s a fortified zone, protected by armed guards, with luxury villas for the bosses and prison-like compounds for the workers. The KNA doesn’t run the scams themselves - they rent out space, provide security, and take a cut. In exchange, they get cash, weapons, and political cover from Myanmar’s military junta. The U.S. didn’t just name the companies. They went after the people: Saw Chit Thu, the KNA leader, and his two sons - Saw Htoo Eh Moo and Saw Chit Chit. All three are now on the OFAC sanctions list. That means any U.S. person who sends them money, even $5, is breaking federal law. Any bank account they hold in the U.S. is frozen. Any crypto wallet linked to them is flagged. And any company doing business with them - even indirectly - risks being cut off from the American financial system.Why This Matters to Americans

You might think, "I don’t trade crypto. This doesn’t affect me." But it does. Every dollar lost to these scams drains money from the U.S. economy. People lose retirement savings. Small businesses lose customer funds. Families lose everything. The Treasury estimates that in 2024 alone, over 100,000 Americans were scammed - many of them elderly, many of them tech-naive. One woman in Ohio lost $87,000 after being told she’d "invest" in a new blockchain-based health platform. She never got a single token. She got a fake website and a dead phone number. These scams also fund violence. The money flowing out of Shwe Kokko doesn’t just line pockets. It buys guns. It pays for border patrols. It keeps the Myanmar military in power. The U.S. is no longer just fighting fraud - it’s fighting a regime that uses crime as a weapon.

What the Sanctions Actually Do

The sanctions aren’t a warning. They’re a shutdown. Here’s what happens when you’re on the OFAC list:- All U.S.-based assets are frozen - bank accounts, crypto wallets, real estate.

- U.S. citizens and companies are banned from doing any business with them - even paying for a coffee.

- Financial institutions must block any transaction that touches a sanctioned entity.

- Crypto exchanges like Coinbase and Kraken are required to flag and freeze any wallet linked to these names.

How This Fits Into Broader U.S. Strategy

This wasn’t a one-off. The U.S. used four different executive orders to justify the action:- E.O. 13851 - Targets transnational criminal organizations.

- E.O. 13694 - Catches cyber-enabled financial attacks.

- E.O. 13818 - Addresses human rights abuses (forced labor, torture).

- E.O. 14014 - Blocks threats to Burma’s stability.

What This Means for Crypto Users

If you trade crypto, this should scare you - and motivate you. These scams prey on people who don’t know how to check a wallet address, verify a project, or spot a fake whitepaper. The U.S. government is now watching every transaction that touches a sanctioned entity. If you send funds to a wallet that’s been flagged - even unknowingly - your own account could be frozen. Here’s what to do:- Always verify the official website of any project before investing.

- Use wallet explorers like Etherscan or Solana Explorer to check where funds are going.

- Never send crypto to a person you met online - no matter how "legit" they seem.

- Report suspicious offers to the FTC at ReportFraud.ftc.gov.

What Comes Next

The Treasury says this is just the beginning. They’ve already started tracking how the KNA moves money through intermediaries in Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam. More names will be added. More wallets will be frozen. And if the Myanmar military is found to be directly funding these operations, they could be next. Experts believe this could trigger a global ripple effect. Other countries - Canada, the EU, Australia - are watching closely. If they follow suit, the entire criminal ecosystem in Southeast Asia could collapse. The scammers have nowhere to hide. Their servers are monitored. Their money is tracked. Their protectors are now targets. This isn’t a war on crypto. It’s a war on crime - using crypto as the weapon to fight it.Are U.S. citizens at risk of being arrested if they accidentally sent crypto to a sanctioned entity?

No, U.S. citizens won’t be arrested for accidentally sending crypto to a sanctioned entity. OFAC sanctions are civil, not criminal. That means you won’t go to jail. But your transaction will be blocked, and your wallet may be flagged. If you realize you sent funds to a sanctioned address, immediately stop all activity and report it to your crypto exchange. You may need to file a self-disclosure with OFAC to avoid future penalties. Ignorance isn’t a defense, but intent is - accidental transfers are handled with warnings, not prosecution.

Can I still use crypto exchanges like Coinbase or Kraken after these sanctions?

Yes, you can still use major exchanges like Coinbase and Kraken. In fact, they’re now required to comply with OFAC sanctions. These platforms have upgraded their screening systems to block transactions to known scam wallets linked to Shwe Kokko and the KNA. If you try to send crypto to a sanctioned address, the exchange will stop it and notify you. Your ability to trade isn’t affected - only your ability to send money to criminal networks.

Why target Myanmar specifically? Isn’t crypto fraud happening everywhere?

Myanmar, especially Shwe Kokko, is the epicenter of this crisis. It’s not just that scams happen there - it’s that they’re run like military operations. The Karen National Army controls the area, uses violence to force people into labor, and has direct ties to Myanmar’s ruling junta. No other country has such a concentrated, state-backed criminal ecosystem built around crypto fraud. The U.S. targeted Myanmar because it’s the most dangerous and organized hub - and taking it down could break the entire model.

How do I know if a crypto project is legitimate and not tied to these scams?

Check three things: First, look for a public, verifiable team with LinkedIn profiles - not just anonymous Telegram handles. Second, verify the smart contract on a blockchain explorer like Etherscan - if it’s unverified or has no code, walk away. Third, search the project’s wallet addresses on OFAC’s sanctions list or use tools like Chainalysis or Elliptic. If any address is flagged, don’t interact with it. Legitimate projects don’t hide. Scams do.

Have any of these scam operators been arrested or extradited?

No arrests have been made yet. The sanctions are designed to cut off their money and operations, not to capture them. The KNA operates in a lawless zone with no extradition treaties. The U.S. is working with Thailand and international law enforcement to gather evidence, but physical arrests are unlikely without a major military or diplomatic shift. For now, the goal is to starve the operation - freeze funds, block access, and force collapse from within.